Glass and steel are similar in many ways. They’re both made from raw materials originally mined from the earth: silica sand, trona, limestone and dolomite in the case of glass, iron ore in the case of steel; those raw materials are completely transformed by heating them to around 1500 degrees centigrade; and both glass and steel can then be repeatedly recycled without losing their extraordinary properties.

Those similarities point to many of the same sustainability issues: around the impacts of raw material extraction and processing; greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions; and the challenges of improving circularity.

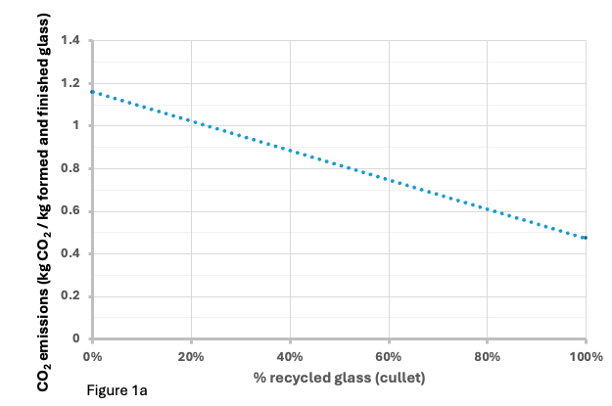

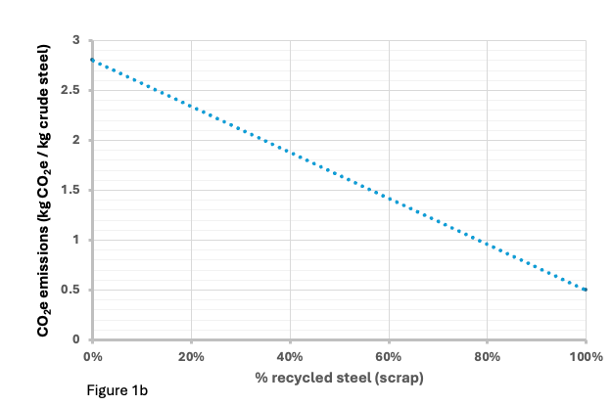

It may not be so surprising then that when you plot the graph of GHG emissions per tonne of finished glass against the proportion of recycled glass (cullet) used for its production, you get a sloping line – just as you do for steel and scrap – as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1, showing the CO2 emissions per kg of glass (figure 1a, on the left) and CO2 e emissions per kg of steel (figure 1b, on the right). The data for glass are for CO2 only, from Sheikh et al (2023)1; the data for steel are for CO2 equivalent, from ResponsibleSteel2.

And the lines slope for the same reasons: less energy is needed, and less process gas is generated to melt cullet than to make new glass from silica sand and carbonates, just as less energy is needed and less process gas generated to melt scrap than to make new steel from iron ore. The more primary material you can replace with cullet, or scrap, the lower the greenhouse gas emissions per tonne of product.

Does that mean that a standard to support GHG emissions reductions in the glass sector needs to be based on a ‘sliding scale’, to account for cullet content, in the same way that it is necessary to account for scrap use in steelmaking?

Probably not.

The reason is simple: the global recovery rate for steel at the end of its life in use is estimated to be around 85%, which is pretty close to the maximum level achievable. The equivalent figure for the recovery and recycling of cullet for glassmaking is nothing like that.

It is true that in some countries up to 95% of the glass used for making bottles and jars, or ‘container glass’, is reported as being recovered for recycling3 – which is even higher than the levels achieved for steel scrap. But for many countries the end-of-life recovery rate for container glass is closer to 50%, with the rest disposed of as waste or used as aggregate. And container glass itself makes up less than half of all the glass produced. When it comes to the recovery and recycling of the ‘flat glass’ used as glazing for buildings or for car windscreens, or to glass fibre, global recycling rates are reported to be nearer 1%.

So, although cullet is a ‘constrained resource’ in the same way that steel scrap is, it is not even close to being fully utilised at the global level.

In other words, whereas steel scrap recovery and recycling in the steel sector is already pretty much maxed out, without the need for additional incentives, the same is not true for glass. And that has major implications for standards.

For the steel sector, where available scrap will be used anyway, simplistic carbon footprint specifications which do not take account of recycled content encourage the redistribution of scrap between different products and undermine efforts to reduce overall GHG emissions. In contrast, in the case of glass, well-designed carbon footprint based measures should result in GHG emissions reductions as intended – whether those reductions are achieved by incentivising cullet recovery and recycling, or by reducing the GHG emissions associated with other aspects of glassmaking.

There are plenty of other questions left to answer. For example, should the same GHG performance levels be specified for container glass and for flat glass – and indeed for other types of glass – or should the levels be different for different manufacturing-, and/or different product categories? Should flat glass GHG emissions intensity figures be specified on a ‘per area’ basis (as is often the case currently), or on a ‘per mass’ basis? Should the use of pre-consumer cullet be given the same recognition as post-consumer cullet?

The new ResponsibleGlass programme is setting out to address these kinds of questions.

It is too early to give any definitive answers – the whole point of multi-stakeholder standards development is to find the answers in discussion with key interest groups and experts. But now is a good time to start thinking about the questions.

- Sheikh, A.Y., Barker, B., Markkanen, S. and Devlin, A. (2023). “Glass sector deep dive: How could demand drive low carbon innovation in the glass industry.” Cambridge: Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL). ↩︎

- ResponsibleSteel International Production Standards version 2.1.1 ↩︎

- The proportion actually recycled may be lower than reported. See Global Recycling League Table Phase One Report, Eunomia (2024) ↩︎